It's Going To Take A lot More Than Hitting The Block Button

on the death of fan/celebrity culture

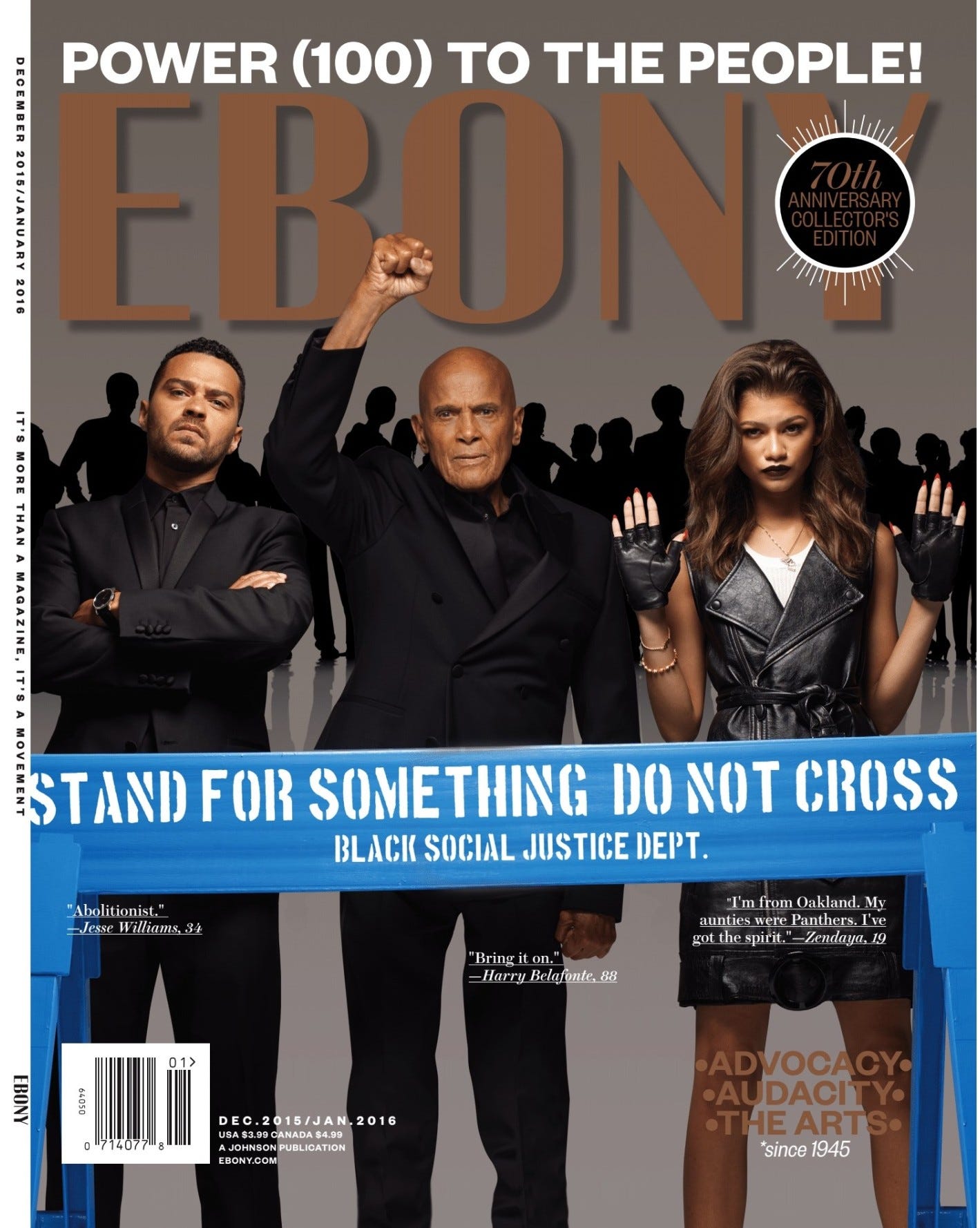

I think about this cover of Ebony Magazine often. The year was 2015, and times were tense. In the sixteen months leading up to the release of this cover, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland1, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, and many others lost their lives at the hands of police brutality. The Black Lives Matter movement was relatively nascent and many people believed that a Trump presidency was unlikely. It feels like this era was a lifetime ago, but I remember when this cover came out and the mixed response it generated on social media. Some folks thought it reflected the times, and others found it to be performative. A couple of Twitter users I followed poked fun at Zendaya, who was not yet a global fashion icon and movie star, for saying, “I’m from Oakland. My aunties were Panthers. I’ve got the spirit.” This cover was Ebony’s Power 100 issue, which honored Bree Newsome, Black Lives Matter, The Fegurson Resistance Movement, and Devin Allen that year. The optics of choosing three fair-skinned celebrities as the face of activism instead of those who risked their lives and livelihood on the frontline were questionable. Nearly ten years later, this cover still represents our collective relationship with celebrity and activism, but the tide is shifting.

Last week, the Met Gala was in full swing, and Zendaya (who doesn’t seem to be embodying that Panther spirit with her silence about what’s happening to the people of Palestine, Congo, and Sudan) was once again crowned the belle of the ball, even serving as co-chair of the event. As much as I love outrageous costumes and pretending I am the fashion police, I opted out of participating in the public discourse this year. When pageantry dominates our newsfeeds in the midst of an attack on people who have nowhere to go, we have to read the room and, at the very least, know when it’s better to leave some things in the group chat. This sentiment was shared by many folks who opted to block celebrities after being disturbed by the display of excessive wealth juxtaposed against protesters in front of The Met and images of slaughtered children in Rafah being posted across social media. While blocking celebrities is certainly a more proactive choice than posting a black square on social media, the work of unpacking how we got here in the first place does not start or end there.

Celebrities account for 0.0086% of the world population, yet they take up so much of our headspace, digital real estate, and, in some cases, money. Personally, I’ve noticed content I make mentioning celebrities, even if I’m critiquing them (which I often do), gets far more engagement than when I’m not talking about someone famous. Celebrities are our common ground. They give us something to talk about at the water cooler, at the bar, when we’re waiting for everyone to log onto the Zoom meeting. We could blame marketing, algorithms, and the media for this, but what seems to be lost in this conversation is that our obsession with the rich and famous reflects what we believe about ourselves and the power we hold. We hold celebrities in high regard because, on some level, we believe that they are better than us. We think they are prettier, thinner, richer, more talented, charismatic, interesting, or worldly. We idolize them as being these all-powerful figures as if we don’t have power ourselves. We project our ideologies onto them even though their core function is to be agents of the very systems of oppression we want them to speak out against. Our perception of celebrities often benefits their personal brand because it keeps the reality of who they are and what they stand for obscured.

Recently, I watched a Doja Cat interview. As an early fan of her work, some of her questionable choices have turned me off of her persona. I wanted to gain an understanding of why she’s like…that. I got my answer when she explained that she doesn’t want politics to enter her personal life— she just wants her life to consist of the direct reality of her friends, family, and making music. This privileged insularity is not unique to her; it is how most celebrities operate, and I would argue that this is the primary power they have. In general, I think we misjudge the power of celebrity. Of course, more visibility and wealth yield more hierarchal power, but it’s a bit paradoxical to call on apolitical hierarchal power as we work toward decentralization. I’m not convinced celebrities resisting or protesting en masse would yield significantly more change. For weeks, we have watched hundreds of thousands of people do exactly that, and our government blatantly ignores disregards, and admonishes it in response. At best, it would inspire other people to get active, which would be amazing, but that is a power we all have.

Historically speaking, it is ordinary people who have made the most movement when it comes to pushing social causes forward. There was no culture of celebrity when abolitionists were fighting for the end of slavery, suffragists for the right to vote, or even when Martin and Malcolm were leading the way for civil rights. Recently, I’ve been reading Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit to get some perspective on how to imagine a better future in such dire times. The passage below is a perfect metaphor for the role we expect public figures to play in pushing forward social causes:

Imagine the world as a theater. The acts of the powerful and the official occupy center stage. The traditional versions of history, the conventional sources of news encourage us to fix our gaze on that stage. The limelights there are so bright that they blind you to the shadowy spaces around you, make it hard to meet the gaze of the other people in the seats, to see the way out of the audience, into the aisles, backstage, outside, in the dark, where other powers are at work. A lot of the fate of the world is decided onstage, in the limelight, and the actors there will tell you that all of it is, that there is no other place.

No matter the details or the outcome, what is onstage is a tragedy, the tragedy of the inequitable distribution of power, the tragedy of the too common silence of those who settle for being audience and who pay the price of the drama.

In the context of celebrity culture, the actors Solnit is speaking about could be celebrities, influencers, or even activists with questionable intentions, and we have been paying the price of the drama. Much of our current era of political activism is influenced by the civil rights movement, and as a result, many people believe that movements need dedicated leaders to be effective. We may not expect them to be movement builders, but our backlash towards their silence implies we expect them to use their platforms to lead their fans and followers. But what if I told you that you are the leader you are waiting for? Solnit underscores this point:

You may be told that the legal decisions lead the changes, that judges and lawmakers lead the culture in those theaters called courtrooms, but they only ratify change. They are almost never where change begins, only where it ends up, for most changes travel from the edges to the center…

How did these stories and beliefs migrate from the margins to the center? Is there a kind of story food chain or dispersal pattern? Can stories be imagined as spreading like viruses or evolving like species to other habitats and other forms? You could even argue that stories spread like fire, except that fire is perhaps the ultimate drama, and stories sneak in while no one is watching. Just as fashions are more likely to originate in the street with poor nonwhite kids, so are new stories likely to start in the marginal zones, with visionaries, radicals, obscure researchers, the young, the poor—the discounted, who count anyway. The routes to the center are seldom discussed or even explored, in part because so much attention is focused on that central stage.

By nature of having wealth and access, celebrities do not exist in the margins Solnit is speaking of. The majority of them are likely being advised by their publicists not to speak out, to wait for things to settle down because our attention spans will eventually move on from Palestine, The Congo, Sudan, Haiti, Tigray, and every other corner of the world in crisis that doesn’t have our full attention and support because the limelight and the stage have blinded us. It happened in 2020, and it’s happening again. Solnit continues:

Americans are good at responding to a crisis and then going home to let another crisis brew both because we imagine that the finality of death can be achieved in life—it's called happily ever after in personal life, saved in politics and religion— and because we tend to think of political engagement as something for emergencies rather than, as people in many other countries (and Americans at other times) have imagined it, as a part and even a pleasure of everyday life.

My hope is that we can use this moment to reflect on how we can stop our attention from being exploited by celebrities, corporations, talking heads, or whoever is not serving us. What changes need to happen in how we move in our day-to-day lives that will destabilize these power imbalances? Instead of focusing on who we are blocking, let’s talk about who we are boosting. What art are you consuming that says something new, necessary, or healing? How can we get people to spend as much time learning about Palestine as they did watching Reesa Teesa so they can stop saying “it’s complicated” and “they don’t have enough information”? How can we raise as much money for aid to the places in the world in crisis as we did for the Renaissance World Tour? Who in our direct community needs to be called in, enlightened, challenged, or informed? It’s going to take a lot more than hitting the block button for us to yield the transformative change we deeply need.

Social media can either be incredibly powerful when used to inform or irreparably harmful when it is used to distract and spread misinformation. Because of this, it’s imperative we extend the actions we take towards change outside of smartphones and parasocial relationships. What’s happening worldwide is not just about ideologies, propaganda, or specific players and participants; it is deeply spiritual. We are being called to reconnect with each other in meaningful ways, to put our feet back on the ground. Many of us have both atrocities and trivialities take up our headspace on a daily basis because that is what social media is designed to do, but I want more of us to think about how this has impacted us on a personal level. In what ways have social media and celebrity culture changed you? What impact has the content created in these spaces had on our mental health? What needs to be spiritually and emotionally recovered after living in the vortex of mass media and smartphones? The death of celebrity culture is going to be a reckoning for fans before it becomes a truly effective reckoning for celebrities. Now, let’s roll up them sleeves and get to work.

RESOURCES

Below is a list of organizations I’ve supported that keep me informed. I’m signed up for their newsletters because social media is a bit too triggering for me these days. Please feel free to drop more in the comments.

The Intercept

Friends of Congo

Darfur Women Action Group

CodePink

US Campaign for Palestinian Rights

Catch me on these digital streets.

Watch My Short Film “One Of The Guys” 🎥

Instagram 🤳🏾

TikTok ⏰

Website 👩🏾💻

Merch 🛍️

💋 ✌🏾

LaChelle

Sandra Bland’s official cause of death was suicide by asphyxiation, though many people believe this to be questionable.

"Historically speaking, it is ordinary people who have made the most movement when it comes to pushing social causes forward."

This line resonated with me the most. These days, on IG, barely any celebrities speak about the atrocities that are happening daily in Palestine, but most of my friends/acquaintances are speaking about it all the time. just because celebrities have fame and wealth, it doesn't mean they have numbers.

That was so cohesive and sharp, thank you. I find what doja cat said a bit paradox, because it is the ‚direct’ politics of the USA that are responsible for the genocide right now (for example), her choice to live the way she lives directly and immediately effect politics. This is what people don’t understand, you cannot be apolitical, every thing you do is political, especially if you have money and influence through the ways you live. To avoid or abstain politics means you don’t want any responsibility concerning a community driven society. And I have always said this: no influencer or celeb has a community, they only have an audience (writing right now about symbolic politics in celeb culture and how that creates an illusion of a world that isn’t living in the present).