Erasure/American Fiction | Book to Screen Vol. 002

How much does integrity cost Black artists?

This will be the last free Book to Screen post because baybee, these take a lot of work! The next two book adaptations I will review are Black Cake by Charmaine Wilkerson and The Changeling by Victor LaValle. Consider upgrading to a paid subscription to gain access.

Erasure has been on my to-read list for twelve years. For TWELVE YEARS, I’ve seen it on the shelves of bookstores and thought, “Eh.. I don’t know”. I need at least two co-signs from trusted sources before picking up a book by an author I’m unfamiliar with. Time is precious, and I try to avoid reading anything that feels like a job to get through, which are exactly the kinds of books the protagonist, Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, writes. As an avid reader, a Black writer, and a disillusioned independent filmmaker, my craft and my relationship with literature are a direct reflection of many of the themes in this book. After watching the film and reading the book, it became clear to me that this story is not intended to be good or bad, high art or lowbrow, coonery, or a well-crafted performance piece. If anything, both Erasure and American Fiction left me with more questions than conclusions about how Black artistry and Black culture intersect and the influence gatekeepers have on our artistic expression.

As usual with this book-to-screen series, I suggest you either read the book or watch the film before reading this. If you’re a no-spoilers person, bookmark this on your Substack app and return after you’ve read and watched. I read the book after watching the film, and I think doing it in this order made me appreciate some aspects of the film I struggled to grasp when watching it the first time. Whether you choose to read the book, watch the movie, or neither first is entirely up to you; proceed with caution.

SPOILERS AHEAD

Erasure

Described as satirical metafiction, Erasure follows Monk, an awkward writer who grapples with his identity and the literary world’s expectations of Black writers (or, in Monk’s case, writers who happen to be Black). Monk is the type of author I loathe; he is verbose and pedantic and takes himself too seriously. Most of his writing is hard-to-digest references to Greek mythology, and as a result, he has never achieved commercial success as an author. It doesn’t help that his work is often sequestered to the African American studies section of bookstores despite not matching the genre. As we learn about Monk’s background, it’s not hard to understand how he ended up this way. The youngest child of an upper-middle-class family, with a live-in housekeeper (Lorraine) and a summer home in the Chesapeake Bay (changed to Martha’s Vineyard in the film), Monk’s family legacy includes three generations of doctors (his grandfather, father, and two siblings, Lisa and Bill). This is the kind of family I associate with The Talented Tenth and Jack and Jill. Monk stands out as the sole artist in the family; he is the special one, the person gifted with high-minded intelligence, and his father’s favorite child. His intellectual snobbery is encouraged by his father, much to the dismay of his siblings. Family dinners get overtaken by mundane academic discourse between Monk and his father. Lisa and Bill are rarely praised and celebrated in the same way Monk is, despite being doctors and Monk’s lack of critical acclaim or commercial success.

Monk’s class background disconnects him from Black cultural norms, which makes him feel othered at times. He doesn’t understand slang and is not the kind of guy who gives a dap or a head nod when he sees a fellow Black man on the street. Given this context, it should be no surprise that he took issue with the runaway success of the book We’s Live In Da Ghetto by Juanita Mae Jenkins (renamed Sintara Golden in the film), which is rife with minstrel-like dialogue and harmful stereotypes of Black Americans.

When Monk’s sister is murdered by an anti-choice lunatic outside of her clinic, he is tasked with taking over her duties of caring for their mother, who soon after is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. With new familial obligations, Monk needs to make some real money fast, and as we’ve established, those boring books aren’t going to help him do that. Out of desperation and bitterness, he decides to take a page out of Juanita Mae Jenkins’s playbook and writes a novel entitled My Pafology (later renamed Fuck) that changes his career and pockets forever.

Monk creates an alias, Stagg R. Leigh, to pen My Pafology, a novel within the novel about a young Black man named Van Go Jenkins. Van Go’s characterization is a one-dimensional caricature of every negative stereotype about Black men. He is a self-hating, misogynistic1 manchild with numerous children named after OTC drugs (Tylenola, Dexatrina, Apsireene, etc.) by multiple women. He is a criminal who still lives at home with his mother (whom he hates) and can’t keep a job because of his poor attitude.

It is believed that My Pafology is a parody of Richard Wright’s novel Native Son2. Van Go is Bigger Thomas’ more flagrant and absurd descendant. I remember reading Native Son for the first time and being unable to put it down. In retrospect, what engrossed me in that novel was how flabbergasted I was by the decisions Bigger made that led to his demise. Though My Pafology is violent, simpleminded, and deeply unserious, it provides Monk the largest advance of his career and the ability to career for his ailing mother. However, this newfound success causes Monk to grapple with creating a piece of work that represents a part of the Black experience that Monk neither identifies with nor believes to be real, despite white gatekeepers heralding it as such.

First, he tries convincing himself that he isn’t selling out; he’s just not turning away a check that he is not in a position to refuse. This stance begins to unravel as he dissects the compositional approach to his work and how it is not something he respects or takes seriously as he works with a white jury of people who shortlist My Pafology/Fuck for a literary award. When he realizes that he has propped up the same artistic traditions he has attempted to challenge by not writing about the Black experience, he concedes that he is indeed a sellout.

My Pafology was not intended to be a work of art reflective of anyone’s true lived experience but rather a fictional device unworthy of dissection. Yet, this doesn’t stop him from accepting a deal to sell the film rights of the book to New Jersey-bred racist Wiley Morgenstein, who insists on meeting Stagg R. Leigh before signing a multi-million dollar check. When Monk (acting as Stagg) orders a gibson and cold carrot ginger soup off of the menu, Morgenstein begins to question if Stagg is “the real deal.” in his mind, Stagg must be a cognac-drinking, fried chicken-eating fugitive (he even jokes that he thought about having their meeting at Popeye’s). It’s a brief exchange that illustrates the monolithic perception racist gatekeepers’ have of Blackness. Everett is very effective at crafting small moments to reflect his broader themes. There are digressions sprinkled throughout the novel that say a lot without over-explaining. He employs Latin phrases like ne te quaesiveris extra (do not seek for things outside of yourself) and ridentem dicere verum quid vetat (what forbids a laughing man to tell the truth), and imaginary conversations between famous artists like this one:

D.W. Griffith3: I like your book very much.

Richard Wright: Thank you.

One of the longest and most interesting digressions is about a Black named Tom who goes on a game show called Virtute et Armis4, where he is forced to put on “makeup” (Blackface) and answer questions like “What is a serial distribution field?” while his white competitor fails to answer simple questions like “name a primary color.” It’s through these choices that Everett makes clear that Monk’s internalized colorblindness and exceptionalism do little to prevent him from wearing a mask and playing the role expected of him by racists in order to thrive.

A lot is going on in this book that feels peripheral to the core message. Monk’s father has a secret child with a white woman (whom Monk tracks down and gives $100,000 out of guilt) and dies by suicide. His relationship with his brother Bill, who struggles with addiction and is not fully accepted by his family for his sexuality, is strained. He endures grief after his sister Lisa is murdered, and his mother’s health begins to decline. His relationships with women are also complicated. Linda (a fellow writer who always wants to smash) craves attention that Monk doesn’t want to give, and his girlfriend Marilyn (changed to Coraline in the film) breaks up with him after he lambasts her for enjoying We’s Live in Da Ghetto. These aspects of the book showcase how Monk’s emotional blocks impede him from connecting with others in meaningful ways — perhaps this mirrors his artistic struggles. He wants to do the right thing, but he is never 100% sure what the right thing is. At just 265 pages, it’s a body of work that packs a punch, and so naturally, the film adaptation had to take creative liberties to ensure the motifs and themes don’t get muddled in its execution.

American Fiction

In February, I saw American Fiction in theaters and had a good ‘ol time. The casting and performances were brilliant. I hard-cackled numerous times and found much of the dialogue to be very pointed and relevant. However, the tone and pacing made it difficult for me to pick up everything writer-director Cord Jefferson was putting down during that first watch. After reading the book and watching the film a second time, I gained a deep appreciation for most of the creative liberties Jefferson took and his overall approach to translating the meta nature of the source material to the screen.

TONE

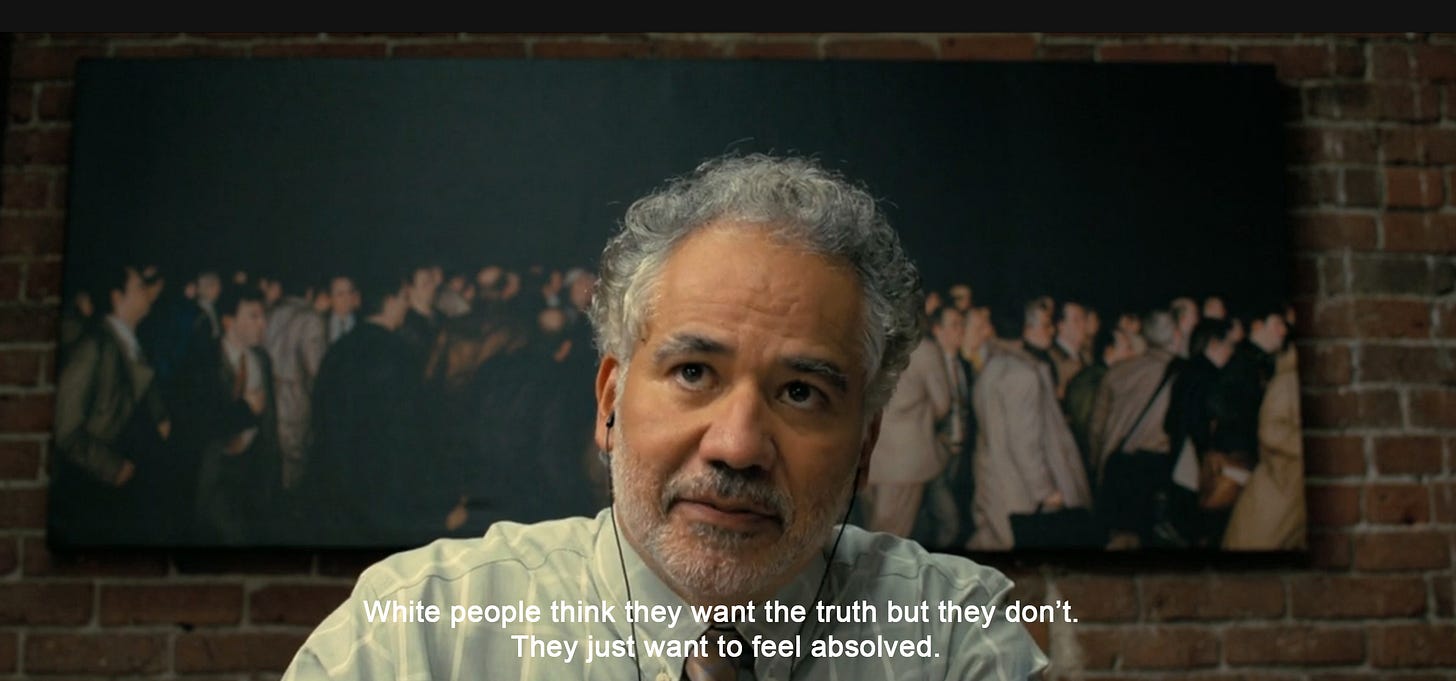

Jefferson sets the thematic and emotional tone with a cold opening of Monk leading a classroom discussion about The Artificial N*gger by Flannery O’Connell. A white student speaks up about being uncomfortable and offended that the n-word is written on the whiteboard and questions why they have to stare at it, to which Monk responds “With all due respect Brittany, I got over it, I’m pretty sure you can too”. The suggestion here is that this white person is uncomfortable, not because the word is making the people who have been oppressed by it uncomfortable, but by being forced to sit with the history of white racism in this country. This is one of the first exchanges in the film where white people center their feelings while ignoring what the Black people in the room think and feel. Another example of this is when Monk and Sintara Golden5 are outnumbered by their fellow (white) jury members who ignore their concerns about Fuck by Stagg R. Leigh. One of the jury members reasons, “I think it’s essential to listen to Black voices right now, right?”— a hilariously ironic line to deliver after invalidating the opinions of the only two Black people in the room. In these instances, Jefferson stays true to the form of Erasure, but there are also choices he makes throughout the film that create more levity than in the book.

Notably, Lorraine shifts from a Mammy-Sapphire hybrid into a loving member of the Ellison family. Her wedding to Maynard gives us one of the most heartful moments of the entire film, a dance break in which everyone (including Monk’s homophobic mother and Bill’s male companions) are basking in joy. Monk, of course, doesn’t partake in the festivities, but this juxtaposition shows how his inability to connect with others and his penchant for being too analytical isolates him.

PACING

The primary drawback I experienced when watching the film the first time was that the pacing felt inconsistent. Specifically, Monk’s relationships with his sister Lisa and his girlfriend Coraline (who share similarities outlined in both the book and the film) felt like they could’ve been more fleshed out.

Lisa’s death felt abrupt and jarring when watching the film for the first time. I understand why it was changed from a murder by an anti-choice crusader. I think keeping her death this way would’ve changed the tone of the film and distracted from the core themes, but the heart attack felt like it came out of nowhere. The book provides exposition that gives more context into who Lisa was and the unique role she played in the family. We get more time with her even though she is still killed off relatively early in the story. The film’s approach to Lisa’s death felt a bit like fridging, which is a term I recently learned while reading

’s newsletter Women's Business" Hip Hop, Rap Beef and Cannon Fodder. Did Lisa have to get killed off to be a catalyst for Monk needing to make more money? Was his mom’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis alone not enough to set this storyline into motion? While I enjoy seeing Tracee Ellis Ross on the big screen, I think there could’ve been a case for omitting Lisa’s character if she was only going to be used as a plot device.Monk’s relationship with Coraline is almost the inverse of what happened with Lisa. The film expands their relationship, and we get to see Monk express tenderness, even in very brief moments. Changing the book Monk and Coraline argue about from We’s Live in Da Ghetto to Fuck deepens their conflict, which is more about how Monk feels about what he’s created than Coraline’s taste in literature. Unlike Monk, Coraline never hid her cards. Monk hides this dirty little secret of a book from everyone; he’s incapable of being vulnerable, and he is tormented by his inauthenticity. Coraline is a defense lawyer who enjoys defending guilty people and challenges Monk by suggesting writers can’t judge their characters if they want to write them well. Coraline maintains a level of neutrality that Monk is incapable of practicing. Jefferson’s choice to change Coraline sleeping with her ex after already dating Monk in the book to telling him about her ex on the day they meet helps reinforce her characteristic of being an open book. But we never hear about this ex-boyfriend again after that scene, so it kind of feels like a plot hole. Perhaps this is the point because Monk’s relationship with Coraline isn’t really about romance; he’s not a romantic. When we see Coraline arriving at Monk’s award ceremony at the end, it’s not because this is some unrealized love story; it’s clear there is no compatibility between them. Coraline emerges in this moment because she is the embodiment of his contradictions, staring back at him while he decides if he should come clean about being Stagg R. Leigh or not.

MY PAFOLOGY/FUCK

My Pafology gets far less screen time than the book gave it, and for a good reason. Instead of diving into the particulars of Van Go Jenkins’s story and the world he inhabits, Jefferson pulls out the most impactful scene where Van Go discovers that Willy, an unhoused alcoholic who roams around his neighborhood, is his father and shoots him. This exchange summarizes Van Go’s entire plight as well as the core stereotype that influences the rest of his behavior, that because he has a father that “ain’t shit,” he “ain’t shit” either. It’s an oversimplification of what leads Black men down dangerous paths. There is no context for generational trauma, systemic racism, and the barriers at play that create men like Van Go because men like Van Go aren’t real. Real people are much more complex than clichés or even the narratives that they believe about themselves.

Jefferson translates the self-referential tone of the book to the screen by placing the characters in the room with Monk, even having them stop in the middle of delivering lines to question the direction Monk is going. I listened to Cord’s interview on Larry Wilmore: Black on Air podcast, where he talks about how he did not expect the actors (Okieriete Onaodowan as Van Go and everybody’s favorite villain, Keith David as Willy) to play their parts straight, and it was a moment where he learned the power of letting actors make their own choices, often they will exceed your expectations. The result is absurd, hilarious, and a perfect reflection of My Pafology without being an on-the-nose interpretation of the book’s version of the novel.

THE ENDING

First, I would like to say that Adam Brody as Wiley Valdespino was absolutely perfect. Changing him from a New Jersey hard-ass to a stereotypical Hollywood dudebro felt more relevant to how the industry functions today, and Brody played up this character in the most comically realistic way. Where the book leaves us to draw conclusions about the direction Monk takes, the film has one last meta moment by showcasing Monk talking with Wiley about options for the ending of the screenplay for Fuck, to which he lands on Monk/Stagg R. Leigh getting shot at the award ceremony by the FBI who thinks he is a real wanted fugitive. Wiley, of course, thinks this is the perfect ending. Monk leaves the studio set as a backdrop of what looks like a plantation house is moved out of his path. Bill picks Monk up from the studio lot and asks if he will make the movie, to which Monk replies, “Unfortunately, yes.” As the two drive off, Monk notices a Black man sitting in the holding area for extras dressed up in what looks like slave garb. The extra throws up the peace sign to Monk, and Monk acknowledges him with a head nod, symbolizing a silent acknowledgment that sometimes, we have to compromise our integrity to get what we need before we can do what we want6. A clever ending that shows us exactly why Cord Jefferson won that Academy Award.

Erasure/American Fiction, Personal Reflections

I left this story with much to unpack about the space I occupy as a Black writer and filmmaker. I’ve talked in length about the drawbacks of Black excellence, palatability, selling out, and when it’s important to gatekeep Black culture and identity, so none of this subject matter is new to me, but the approach to this story has turned many of those ideas inside out. The primary questions being asked in this book and film are: Is it possible to maintain integrity as a Black artist and thrive in spaces that have been designed to appeal to white sensibilities? When Black artists “sell out,” does it set the culture back, or is it a gotcha moment that allows (some of) us to profit off of the ignorance of white gatekeepers? Neither Erasure nor American Fiction attempts to answer these questions, which is surely the point.

As Hollywood and other creative industries make marginal strides toward improving DEI, Black artists continue to face this conundrum of compromising their authenticity to appease the expectations of people who are disconnected from our culture and fully uninterested in doing the work required to be tapped-in allies. Whiteness7 is inherently narcissistic and delusional; it emboldens people with a built-in superiority complex to believe their perspective is always valuable. It finds pleasure in gawking at the oppression it has created and continues to uphold. It lacks the self-awareness to know when it’s inappropriate to make certain calls. It has no curiosity about how intricate, diverse, and expansive Black lives can be because confirmation bias is its touchstone. All of this creates an environment where most, if not all, of the images we see of ourselves are diluted through the lens of whiteness.

Throughout the film, Monk is often found watching images of Black people on TV, such as a scene from Get Rich or Die Tryin’ and a commercial for “Black Stories Month,” which features a montage of notable Black films where people are being shot, doing drugs, and participating in violence. While it is easy to reduce these images to stereotypes, it feels unfair not to acknowledge that socioeconomic disparities have made many stories like these lived realities for Black folks who have endured unfathomable hardship. It begs the question, is this kind of art a reflection of the culture, or does it influence the culture and how we see ourselves? And for those of us it does not influence, how much of that is due to class privilege, like the kind Monk benefits from? I think what matters most is portraying Black life with nuance and also expanding the depictions of us on the screen beyond tropes that get upheld as truth. This is true for both negative and positive depictions; going too far in either direction flattens our humanity (word to Kathleen Collins).

There is an underlying sentiment that marginalized folks should just be happy to be in the room, which makes selling out something all of us have to do on some level in order to survive in these spaces. Maybe selling out doesn’t look like writing a book like My Pafology, but it could be any instance of shifting your ideas to make them easier to understand for people who aren’t your core audience but will ultimately decide if your story is worth being told. The sad reality is the depictions we see of ourselves on the screen will never be as multitudinous as we know ourselves to be, so long as they are shepherded by people who are not from our community (or elite Black people who contort themselves into boxes to fulfill capitalistic agendas).

It is still incredibly rare for me to watch a film or TV show with a predominately Black cast that feels relatable. I heed Toni Morrison’s advice and write authentic stories I want to see. I try not to give in to my anxieties about the feasibility of bringing these stories to life with limited access, capital, and visibility. I’ve come to accept that the path of authenticity will be much more challenging and, likely, way less lucrative, but that should not be a deterrent. What will ultimately empower me is building an audience of supporters that will make me less dependent on people my stories are not intended for. To that, I say thank you to anyone who read this all the way through — you remind me that my voice, as a Black woman writer, matters8.

Catch me on these digital streets.

Watch My Short Film “One Of The Guys” 🎥

Instagram 🤳🏾

TikTok ⏰

Website 👩🏾💻

Merch 🛍️

💋 ✌🏾

With love,

LaChelle

Content warning: the My Pafology section of Erasure contains instances of SA.

It’s also worth noting that Monk’s last name, Ellison, is taken from Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright’s protégée and author of Invisible Man, which has similar themes to Erasure.

Director of the most racist film ever made, Birth of a Nation (1915)

A motto on the Mississippi coat of arms which translates “by valor and arms.”

Shifting the jury from all-white (except for Monk) in the book to mostly white, with just Monk and Sintara Golden as the sole Black people, was a brilliant choice. The exchange between Monk and Sintara reinforces Monk’s hypocrisy when he realizes that he judged her book after only reading a few excerpts and assumes that she must not have done thorough research based on the dialogue.

The Johnnie Walker analogy that Monk’s agent makes is another example of this.

As in a system of oppression, an ideology and/or a type of behavior

This newsletter has way too many footnotes, like Monk’s books. My apologies 🤣

Wonderful essay! I agree with the points you made and I saved reading this essay until I watched the film lol. Thank you!🫶🏾